Although Pittsburgh recently has been named the new “In” city by The Washington Post, it has taken many, many years of redevelopment and progress to go from a city on the verge of implosion, with the mass exodus of the steel industry, to a hub for medicine, technology and industry. The center of the American steel industry, Pittsburgh was a city engulfed by its own industrialism. After the Civil War, Anthony Trollope, the noted British novelist, wrote, “Pittsburgh, without exception, is the blackest place which I ever saw, the site is picturesque, even the filth and wondrous blackness are picturesque… I was never more in love with smoke and dirt than when I stood and watched the darkness of night close in upon the floating soot which hovered over the city.” There was, however, a time when Pittsburgh came very close to escaping the black smoke for an architectural and cultural renaissance spearheaded by Edgar Kaufmann and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Although Pittsburgh recently has been named the new “In” city by The Washington Post, it has taken many, many years of redevelopment and progress to go from a city on the verge of implosion, with the mass exodus of the steel industry, to a hub for medicine, technology and industry. The center of the American steel industry, Pittsburgh was a city engulfed by its own industrialism. After the Civil War, Anthony Trollope, the noted British novelist, wrote, “Pittsburgh, without exception, is the blackest place which I ever saw, the site is picturesque, even the filth and wondrous blackness are picturesque… I was never more in love with smoke and dirt than when I stood and watched the darkness of night close in upon the floating soot which hovered over the city.” There was, however, a time when Pittsburgh came very close to escaping the black smoke for an architectural and cultural renaissance spearheaded by Edgar Kaufmann and Frank Lloyd Wright.

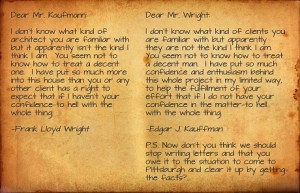

Born on June 8, 1867 to an educated man and a local schoolteacher, it was Frank Lloyd Wright’s set of Froebel Gifts, given to him at the age of nine, that he attributed his success as an architect to. Edgar J. Kaufmann, conversely, was born to a wealthy Jewish-German American family in Pittsburgh, in 1885. His business success was thanks to attending Shady Side Academy and Yale. Each man was fiercely stubborn and forward-thinking and their relationship would fuel some of Wright’s most prolific and largely un-built designs. At the center of their tumultuous and lifelong friendship was the industrial epicenter that Edgar called home: Pittsburgh.

Born on June 8, 1867 to an educated man and a local schoolteacher, it was Frank Lloyd Wright’s set of Froebel Gifts, given to him at the age of nine, that he attributed his success as an architect to. Edgar J. Kaufmann, conversely, was born to a wealthy Jewish-German American family in Pittsburgh, in 1885. His business success was thanks to attending Shady Side Academy and Yale. Each man was fiercely stubborn and forward-thinking and their relationship would fuel some of Wright’s most prolific and largely un-built designs. At the center of their tumultuous and lifelong friendship was the industrial epicenter that Edgar called home: Pittsburgh.

The Kaufmanns, Edgar J. and Liliane, owned a department store in downtown Pittsburgh, named appropriately, Kaufmann’s. Kaufmann’s was a consumer/cultural haven that housed, at one point or another, a hospital, a Carnegie Library branch, eight restaurants, a hardware store, an art gallery and an Elizabeth Arden salon. The department store was a hub of retail activity and even fostered public education. People could attend free exhibitions and lectures on a wide range of contemporary topics. Kaufmann’s even staged its own International Exposition of Industrial Arts, after the trend-setting exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Art in Paris in 1925.

The Kaufmanns, Edgar J. and Liliane, owned a department store in downtown Pittsburgh, named appropriately, Kaufmann’s. Kaufmann’s was a consumer/cultural haven that housed, at one point or another, a hospital, a Carnegie Library branch, eight restaurants, a hardware store, an art gallery and an Elizabeth Arden salon. The department store was a hub of retail activity and even fostered public education. People could attend free exhibitions and lectures on a wide range of contemporary topics. Kaufmann’s even staged its own International Exposition of Industrial Arts, after the trend-setting exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Art in Paris in 1925.

Edgar Kaufmann, Jr. shared his parents’ vision to bring good design to the masses. He was an architecture apprentice at Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s summer home and progressive design school, when his parents decided to build themselves a new summer home. The Kaufmann’s owned a large parcel of land, several hundred acres, that they used as a mountain retreat for their employees. Unfortunately, during the Depression, the employees were unable to afford the $1 it cost to take the train to the Kaufmann’s retreat. Left with a large mass of pristine forest, the Kaufmann’s contracted Frank Lloyd Wright to design a summer home to overlook the 30-foot waterfall on the property. Wright, instead, chose to design the house to sit over top of the waterfall, blending into the hillside. It’s said the Kaufmann’s initial reaction was that you couldn’t see the waterfall from the house, to which Wright quipped, “I want you to live with the waterfall, not just to look at it, but for it to become an integral part of your lives.” He named it Fallingwater. Construction was completed in 1937, and the building immediately came to the attention of the American public. It was featured in a 12-page spread in The Architectural Forum, as well as TIME and LIFE. The Museum of Modern Art also debuted an exhibit about the house. And, thus, their relationship was cemented.

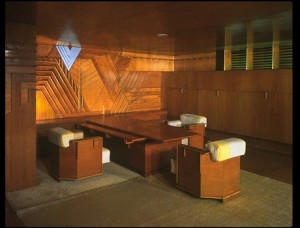

Kaufmann commissioned Wright to develop many other designs for him. Wright designed Edgar’s office in the department store. He was also responsible for a few other projects that, unfortunately, were never built, due to funding or zoning constraints. There was a parking garage that [was] to go next to the department store that looked a lot like the Guggenheim Museum. Then, a planetarium. He designed a twelve-story apartment building to be built into the side of Mount Washington; eight floors [were to be] above ground and four [were to be] built into the mountain. The design was seen again in 1990 when a Pittsburgh Architectural firm unsuccessfully attempted to complete the long-forgotten plans. It was his greatest un-built design of all, however, that could have changed the fate of Pittsburgh forever.

Kaufmann commissioned Wright to develop many other designs for him. Wright designed Edgar’s office in the department store. He was also responsible for a few other projects that, unfortunately, were never built, due to funding or zoning constraints. There was a parking garage that [was] to go next to the department store that looked a lot like the Guggenheim Museum. Then, a planetarium. He designed a twelve-story apartment building to be built into the side of Mount Washington; eight floors [were to be] above ground and four [were to be] built into the mountain. The design was seen again in 1990 when a Pittsburgh Architectural firm unsuccessfully attempted to complete the long-forgotten plans. It was his greatest un-built design of all, however, that could have changed the fate of Pittsburgh forever.

In the 1930s and ’40s, Pittsburgh wanted to revitalize what is now known as “The Point.” At the time, it was a bustling cluster of train yards, factories and an incredibly inefficient road system, bringing drivers over the Manchester and Point bridges in a way that left no room to account for traffic. The Allegheny Conference for Community Development became the force behind the changes that were to be made to downtown Pittsburgh. Edgar J. Kaufmann sat on the board and chaired the committee assigned to look into the problem at The Point.

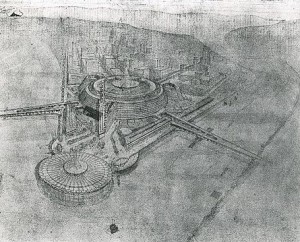

By April 1947, Wright finished his first set of architectural drawings for the site. Wright’s first concept, which he presented under the title “For the Allegheny Conference—Cantilever Development in Automobile-Scale of Point Park, Pittsburgh”, called for a circular concrete and steel building of mammoth dimensions: one-fifth of a mile in diameter and 175 feet tall, the building would be capable of holding one-third of the city’s population. The entire structure was wrapped by a spiraling roadway that Wright called the “Grand Auto Ramp,” which accommodated traffic in both directions and would have been four and a half miles long. Wright’s drawings for the project were enormous: over eight feet long by almost five feet high.

By April 1947, Wright finished his first set of architectural drawings for the site. Wright’s first concept, which he presented under the title “For the Allegheny Conference—Cantilever Development in Automobile-Scale of Point Park, Pittsburgh”, called for a circular concrete and steel building of mammoth dimensions: one-fifth of a mile in diameter and 175 feet tall, the building would be capable of holding one-third of the city’s population. The entire structure was wrapped by a spiraling roadway that Wright called the “Grand Auto Ramp,” which accommodated traffic in both directions and would have been four and a half miles long. Wright’s drawings for the project were enormous: over eight feet long by almost five feet high.

The proposal was ultimately rejected because of concerns about the plan’s economic viability and architectural feasibility. There was also no plan for how traffic access to the bridges would be handled. The proposal also conflicted with existing plans to build a park at the site that would preserve the historic structures and artifacts, including the Fort Pitt blockhouse from 1764. Wright felt the urge for preservation was misplaced, saying, “As I see it, Pittsburgh needs no such Historian. Pittsburgh needs imaginative, creative sympathy for the living and I am eager to do something constructive and joy-giving for the Pittsburgh people. I thought that was my commission.”

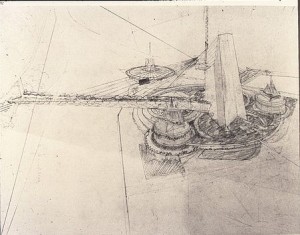

Wright then did something that went against his very core in late 1947; he went back and changed his vision. He retooled the design and showed it to officials from the Allegheny conference at Taliesin in January 1948. The round structure from the original design was replaced by a 1,000-foot tower to be called the Bastion. Two stayed-cable bridges, which would require [the] use of pre-stressed concrete, an experimental material at the time, would cross the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, emerging from the arrowhead–shaped structure, which would contain a traffic interchange. The central tower offered a viewing platform and would project light and sound spectacles and give Pittsburgh a structure similar to the Eiffel Tower. Again, Wright’s proposal was rejected due to concerns with construction, materials and cost. The second proposal would cost upwards of $150,000,000 at the time, the equivalent of $1.45 billion today. The state was, at the time, spending almost that much, $100,000,000, on the Penn-Lincoln Parkway, or 376 as we know it today. Wright was furious, and wrote “… Is it impractical to spend several hundred million to further your culture ,which will survive good or bad, long after the Parkway has collapsed?”

Wright then did something that went against his very core in late 1947; he went back and changed his vision. He retooled the design and showed it to officials from the Allegheny conference at Taliesin in January 1948. The round structure from the original design was replaced by a 1,000-foot tower to be called the Bastion. Two stayed-cable bridges, which would require [the] use of pre-stressed concrete, an experimental material at the time, would cross the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, emerging from the arrowhead–shaped structure, which would contain a traffic interchange. The central tower offered a viewing platform and would project light and sound spectacles and give Pittsburgh a structure similar to the Eiffel Tower. Again, Wright’s proposal was rejected due to concerns with construction, materials and cost. The second proposal would cost upwards of $150,000,000 at the time, the equivalent of $1.45 billion today. The state was, at the time, spending almost that much, $100,000,000, on the Penn-Lincoln Parkway, or 376 as we know it today. Wright was furious, and wrote “… Is it impractical to spend several hundred million to further your culture ,which will survive good or bad, long after the Parkway has collapsed?”

The area was opened up for business development, revitalizing the downtown area of Pittsburgh, and The Point became Point State Park, preserving the Fort Pitt blockhouse and three bastions of the fort. The area also is open to recreational use, notably the Pittsburgh Regatta and the Three Rivers Arts Festival, which, together, bring thousands of people into the city each year. Areas adjoining the park that were condemned to permit commercial development are now home to thriving businesses, most notably Gateway Center. Although Kaufmann’s and Wright’s efforts to rebuild downtown Pittsburgh as a world class cultural and business center were unsuccessful; over the years, the area has become home to three major sports arenas, corporate headquarters, a cultural district with no less than five theatres and has helped Pittsburgh to be repeatedly named “The Most Livable City in America.”

Sources: Frank Llloyd Wright Foundation, The Pittsburgh Post Gazette, Carnegie Magazine, io9, Wikipedia, Fallingwater, The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

Images courtesy of Matthew Field and the Victoria and Albert Museum.